History of the Ballinasloe October Fair

by Damian Mac Con Uladh

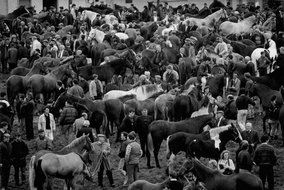

The Ballinasloe October Fair is one of the oldest fairs in Ireland, at one stage renowned as the largest and greatest in all of Europe. While now predominantly associated with the horse, in its heyday the October Fair was an agricultural event of much greater significance, serving as a market for the sale of cattle and sheep by the farmers of the West to their counterparts in the East of Ireland. Indeed, in the London Times of 1801 and 1804, the October Fair was referred to as the “Great Cattle Fair” of Ballinasloe. It is only since the early twentieth century that the fair has become exclusively associated with the horse.

Very little is known about the origins of the Ballinasloe October Fair, as there is little in terms of documentary evidence referring to its early development. In the past, fairs and markets were such a common feature of life in Ireland that contemporary observers perhaps felt little need to make special reference to them.

Very little is known about the origins of the Ballinasloe October Fair, as there is little in terms of documentary evidence referring to its early development. In the past, fairs and markets were such a common feature of life in Ireland that contemporary observers perhaps felt little need to make special reference to them.

A range of other clues point to the fact, however, that the Fair is indeed ancient in origin. The most obvious is provided by the town’s original name in Irish, Béal Átha na Sluaighe, which translates as the “Ford-Mouth of the Hostings”. The “ford-mouth” refers to the crossing point the location offered over the River Suck and the “hostings” to those crowds, possibly military, who gathered to do just that. Strategically located on the crossing from West to East, the desire to defend Connacht led both Irish king and Norman baron to fortify it. Thus, Ballinasloe provided a convenient and safe centre for the sale of livestock from Connacht to Leinster. In other words, animals raised in the West could be easily sold on to graziers from the East for fattening.

The abundant evidence provided by nineteenth-century accounts in newspapers and travel literature make it undoubtedly clear that the Ballinasloe October Fair was one of the greatest and renowned in Ireland and beyond. Indeed, the London Times described the Ballinasloe October Fair as “the largest of its kind in Europe” (1804), “the greatest in the British empire” (1816), and “the greatest one-day fair in Ireland” (1829).

The abundant evidence provided by nineteenth-century accounts in newspapers and travel literature make it undoubtedly clear that the Ballinasloe October Fair was one of the greatest and renowned in Ireland and beyond. Indeed, the London Times described the Ballinasloe October Fair as “the largest of its kind in Europe” (1804), “the greatest in the British empire” (1816), and “the greatest one-day fair in Ireland” (1829).

The emergence of the modern fair is inexorably linked with the arrival to the Ballinasloe area of a family, descended from French Huguenot stock, which would dominate Ballinasloe for over two hundred years – the Trench family, or the Earls of Clancarty as they would later become known. The first, Frederick Trench died in 1669 and his son, also Frederick, actively helped the forces of William of Orange at the Battle of Aughrim (1691) against the army of James II. After the battle, he bought 200 acres around Ballinasloe for the princely sum of £70! The Trenchs continued to buy up property and entered some strategic marriages. Richard Trench, MP for County Galway in “Grattan’s” Parliament, voted in favour of the Act of Union with the United Kingdom in 1800 and was rewarded with the peerage of the Earldom of Clancarty.

By virtue of the fact that it came to own the land and the town in which the Ballinasloe fair took place, the Trench family was in a position to formalise and regularise it. Indeed, in 1757 Richard Trench applied for and received letters patent for the right to hold annual fairs in Ballinasloe on May 17 and July 13 (while Ballinasloe is now famous for its October Fair only, in the past the town also hosted fairs in the other months of the year, the May Fair and the July Wool Fair being the most important of these). It is likely that the Trench's did the same with regard to the October Fair, for they seemed to hold particular rights over it: in 1813, for example, a member of the family in his role as “Baron of the Fair” banned the Fair from beginning on a Sunday for religious reasons. In addition, the October Fair was actually held inside the Clancarty estate of Garbally, the “Race Park” being the main trading arena. A report from 1810 provides an impression of the spectacle that was the October Fair:

By virtue of the fact that it came to own the land and the town in which the Ballinasloe fair took place, the Trench family was in a position to formalise and regularise it. Indeed, in 1757 Richard Trench applied for and received letters patent for the right to hold annual fairs in Ballinasloe on May 17 and July 13 (while Ballinasloe is now famous for its October Fair only, in the past the town also hosted fairs in the other months of the year, the May Fair and the July Wool Fair being the most important of these). It is likely that the Trench's did the same with regard to the October Fair, for they seemed to hold particular rights over it: in 1813, for example, a member of the family in his role as “Baron of the Fair” banned the Fair from beginning on a Sunday for religious reasons. In addition, the October Fair was actually held inside the Clancarty estate of Garbally, the “Race Park” being the main trading arena. A report from 1810 provides an impression of the spectacle that was the October Fair:

“Ballinasloe, Oct. 5th. Yesterday the Earl of Clancarty, according to an annual custom, threw open his extensive park at Garbally, for the reception of the various flocks of sheep that compose this celebrated and extensive mart. By sun-rise nearly a hundred thousand head of sheep, by the skill and activity of Irish shepherds, were variously arranged in their respective columns (without the division of a single hurdle), forming, by their disposition and surrounding scenery, one of the most picturesque and gratifying national spectacles that could possibly be conceived. The continued fineness of the weather added much to the general effect. Full 44,000 sheep were sold in the early part of the day. In the afternoon the prices began to decline; and this morning the best wethers fell from £3 to £2 13s. per head, and the sales were slack at these reduced prices.” (The Times, 19 October 1810)

The October Fair thrived in the nineteenth century, developing into one of the greatest and most famous fairs of its kind in Ireland, Britain and the Continent. It was a vital link in the human food chain, supplying the larger and more prosperous farmers of the Leinster with young cattle and sheep reared in Connacht. Statistics on the number of cattle and sheep sold are testimony to the fair’s size and development: in 1790, 7,782 cattle and 68,095 sheep changed hands; in 1856, at the peak of its success, sales amounted to 20,000 head of cattle and 99,658 sheep. From today’s standpoint it is near impossible to imagine the logistics of transporting cattle and sheep to and from Ballinasloe manually. In 1833, the novelist Maria Edgeworth encountered the multitudes of people and sheep returning from the fair. She wrote to a friend:

“I cannot tell you – and if I could you would think I exaggerated – how many hours we were in getting through the next ten miles; the road being continually covered with sheep, thick as wool could pack, all ‘coming from’ the sheep-fair of Ballinasloe [which] … we now found had taken place the previous day. I am sure we could not have had a better opportunity and more leisure to form a sublime and just notion of the thousands and tens of thousands which must have been on the field of sale. This retreat of the ten thousand never could have been effected without the generalship of these wonderfully skilled shepherds, who, in case of any disorder among their troops, know how dexterously to take the offender by the left leg or the right leg with their crooks, pulling them back without ever breaking a limb, and keeping them continually in their ranks on the weary, long march.” (Augustus J. C. Hare, The Life and Letters of Maria Edgeworth, Vol. 2, 1894)

The emergence of the Ballinasloe Agricultural Show is also due to the Clancartys. The family had always taken an interest in agricultural improvements, and sponsored the housing of the Farming Society of Ireland in Ballinasloe. In 1840 the Ballinasloe District Agricultural Society was formed. Amid great fanfare, in 1845 its headquarters, the Agricultural (now Town) Hall was opened on “Farming Society Street” (now Society Street). The Illustrated London News described the scene:

“The preparations for the show and its attendant festivities are on a scale of great magnitude. Six acres have been taken off the ample proportions of the fair-green and enclosed with comfortable sheds and stalls for the bloated beasts which agricultural societies delight to honour, whilst the central space is reserved for novel farming implements, with all their intricacy of cog wheel, tooth, and rack. A handsome show house has also been erected for the exhibition of grasses, seeds, flax, useful plants, and esculents. Bordering on one side of this enclosure stands the new Agricultural Hall, a vast building of cut stone, just completed or the occasion, and finished in a style of great comfort, solidity, and good taste. Exclusively of other apartments, kitchens, boiler-house, &c., it contains a magnificent room, 150 feet long, by 70 feet wide, extremely lofty, which is the intended scene of feasting and banqueting.” |

Depending on wider economic conditions, the October Fair could secure a future for for thousands of poor Connacht tenant farmers, or spell their ruin. A depression in the national or indeed wider European economy could have direct repercussions for those attending the Fair. A bad fair invariably meant that the tenant farmers of Connacht had no means to pay their rents, which inevitably meant eviction and impoverishment. In the “calamitous year” of 1816, as a result of the economic downturn that followed Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, the Fair “suffered considerably in the actual state of general distress” with prices running “ruinously low”. In 1822 the Times reported: “By many is the approaching fair regarded as one of the greatest moment, and with trembling anxiety they await a result which may lead to a train of circumstances either of a favourable or highly embarrassing nature.” Six years later, in 1828, the local Western Argus contrasted the “lowering downcast looks” of the Connacht farmers which “proclaimed the deepest apprehension” with the “quizzical glances of the sky-blue gentry from Leinster”.

While fairs are primarily associated with the buying and selling of livestock, in the past they had a much greater and wider significance in that they served important social, cultural and political functions. Fairs brought thousands of rural dwellers into towns and thus into contact with the wider world. Attending a fair like the Ballinasloe October Fair exposed country people to new products, goods, inventions, attractions, and ideas. In a practice that continued up to the 1960s, Dublin establishments temporarily “set up shop” in the town for Fair week. County Fair Day, for example, was an occasion for matchmaking: poorer farmers slapped hands on dowries and “married off” their daughters. Culturally, fairs were places attended by all sorts of performers, such as musicians, dancers, strongmen, and magicians, as well as the scenes of spectacular shows of the wonderful and the bizarre. In 1829, for example, fairgoers could inspect the “beautiful race mare Pincussion commonly called Creeping Jenny, with seven legs shod and stands on six feet, the seventh far advanced and eighth growing, fifteen hands high”. This horse reportedly won the City Plate at Canterbury in 1823, and 25 Guinea Stakes at Newmarket the following year. Visitors to the town were also invited to inspect the 22-year-old “small Lilliputian or Whistling Man of the Wood, weighing in at one pound and 8 ounces”. And then as now amusements were a major pull factor, and it was at the October Fair that many young children encountered funfair wonders. And at the political level, fairs allowed the major political issues of the day to be discussed and fought out: for example Wolfe Tone attended the October Fair in order to meet with his Connacht supporters, and in the 1820s, the issue of Catholic Emancipation was hotly debated between supporters of Daniel O’Connell and the Clancarty family.

The Ballinasloe Fair thrived in the days before the arrival of modern forms of transport. As each new mode of transport reached the town, in effect reducing geographic distances, the strategic location of the place decreased correspondingly. In 1828, Ballinasloe became the terminus of the Grand Canal, liking it with Dublin. In 1856, the railway arrived, ensuring that livestock could now be exported from the West much easier and, more importantly, at any time. And with the development of road transport in the twentieth century, the increased mobility of farmers, and indeed of people in general, undermined the whole importance of fairs. And the mechanisation of warfare and agriculture devalued the importance of the horse considerably. In summary, with each step in the industrialisation of all walks of life, the importance of fairs declined correspondingly.

As the October Fair, like all fairs across Ireland, declined in importance from the mid-twentieth century onwards, attempts were made to revitalise it. In 1948 a committee was formed that organised a carnival to coincide with the Fair and the Show. Thanks to the efforts of this committee and those of the long-established Show Society, the Ballinasloe October Fair has managed to survive where many others have faltered and vanished.

While fairs are primarily associated with the buying and selling of livestock, in the past they had a much greater and wider significance in that they served important social, cultural and political functions. Fairs brought thousands of rural dwellers into towns and thus into contact with the wider world. Attending a fair like the Ballinasloe October Fair exposed country people to new products, goods, inventions, attractions, and ideas. In a practice that continued up to the 1960s, Dublin establishments temporarily “set up shop” in the town for Fair week. County Fair Day, for example, was an occasion for matchmaking: poorer farmers slapped hands on dowries and “married off” their daughters. Culturally, fairs were places attended by all sorts of performers, such as musicians, dancers, strongmen, and magicians, as well as the scenes of spectacular shows of the wonderful and the bizarre. In 1829, for example, fairgoers could inspect the “beautiful race mare Pincussion commonly called Creeping Jenny, with seven legs shod and stands on six feet, the seventh far advanced and eighth growing, fifteen hands high”. This horse reportedly won the City Plate at Canterbury in 1823, and 25 Guinea Stakes at Newmarket the following year. Visitors to the town were also invited to inspect the 22-year-old “small Lilliputian or Whistling Man of the Wood, weighing in at one pound and 8 ounces”. And then as now amusements were a major pull factor, and it was at the October Fair that many young children encountered funfair wonders. And at the political level, fairs allowed the major political issues of the day to be discussed and fought out: for example Wolfe Tone attended the October Fair in order to meet with his Connacht supporters, and in the 1820s, the issue of Catholic Emancipation was hotly debated between supporters of Daniel O’Connell and the Clancarty family.

The Ballinasloe Fair thrived in the days before the arrival of modern forms of transport. As each new mode of transport reached the town, in effect reducing geographic distances, the strategic location of the place decreased correspondingly. In 1828, Ballinasloe became the terminus of the Grand Canal, liking it with Dublin. In 1856, the railway arrived, ensuring that livestock could now be exported from the West much easier and, more importantly, at any time. And with the development of road transport in the twentieth century, the increased mobility of farmers, and indeed of people in general, undermined the whole importance of fairs. And the mechanisation of warfare and agriculture devalued the importance of the horse considerably. In summary, with each step in the industrialisation of all walks of life, the importance of fairs declined correspondingly.

As the October Fair, like all fairs across Ireland, declined in importance from the mid-twentieth century onwards, attempts were made to revitalise it. In 1948 a committee was formed that organised a carnival to coincide with the Fair and the Show. Thanks to the efforts of this committee and those of the long-established Show Society, the Ballinasloe October Fair has managed to survive where many others have faltered and vanished.

Damian Mac Con Uladh lives in Greece and writes for The Irish Times.