Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Aug/Sept 2017 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)Duggan, the sainted, whose keen eyes alert Kept watch o’er his flock in historic Clonfert. Ballinasloe has a Duggan Avenue and a Duggan Park. What do we know of the man who was Bishop of Clonfert from 1872 to 1896 and gave his name to those places? Patrick Duggan was born on 10th November 1813 in Cummer near Tuam. The eldest of four children, his father farmed 125 acres in the parish of Milltown. Brought up in the house of his maternal uncle Patrick Canavan, parish priest of Cummer, he entered St. Jarlath’s College, Tuam, in 1829 before moving on to Maynooth in 1833 where he was ordained in 1841.

He served as curate to his uncle before the latter became mentally incapacitated in 1847, thereafter as administrator and eventually as parish priest following Canavan’s death in 1856. Duggan as a young cleric bore daily witness to the horrors of the Great Famine, an event that was to have a profound affect on his political thinking and steered him towards the radical wing of Irish nationalism. Despite having no pastoral experience outside of the parish of Cummer, Duggan was nominated bishop to the adjacent Diocese of Clonfert in September 1871, and consecrated the following January in the convent chapel of the Sisters of Mercy, Loughrea. Undoubtedly, he owed his appointment to the recommendations of two former Maynooth classmates of his, John MacEvilly, Bishop of Galway, and Edward McCabe, Vicar General to the Archdiocese of Dublin. Almost immediately on assuming office he became embroiled in the controversy surrounding a parliamentary by-election, which resulted in a court appearance on a criminal charge and his subsequent acquittal, an episode to be covered in detail in a later article. One of the first acts of his episcopate was to establish a secondary day school for boys in Ballinasloe. Known as St. Michael’s Seminary, it occupied two adjoining, three-storey houses (latterly identified as Earls’s Flats) in Bridge Street. It continued to operate until St. Joseph’s Diocesan College opened at The Pines in Creagh in 1901. The second year of his episcopate saw Duggan set up the Confraternity of the Holy Family in Ballinasloe, an association dedicated to promoting monthly reception of the Eucharist, it continued to flourish up to the 1960s. He was also instrumental in founding the Ballinasloe Total Abstinence Association in 1877. It had a chequered existence and was superseded by the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association early in the last century. An innovation Duggan introduced to the diocese was the construction of curates’ houses. His attempts, however, to build a cathedral at Loughrea were frustrated by the Marquess of Clanricarde, a major landowner in the area. His sympathies were entirely with the aims (and perhaps even the methods!) of the Land League. During the period of the infamous Woodford evictions, William O’Brien MP was on trial at Loughrea for attendance at a banned meeting. Duggan had O’Brien and his defence counsel Tim Healy stay with him at his residence in Bride Street. While they were at dinner one evening, Duggan received his copy of the papal rescript condemning the Plan of Campaign. His reaction to the document could be described as disdainful. Turning to his general factotum, he remarked: “Mike, kill another pig!” Over several decades, Duggan was a regular contributor to a variety of journals and newspapers. An avid reader, his tastes in literature were unsophisticated, his favourite work of fiction being “The Count of Monte Cristo”, a novel he re-read every year after its publication in 1846. Notwithstanding his fluency in Irish, he disapproved of efforts to revive the language which he somehow regarded as a cause of the misfortunes of the Irish people. Though a teetotaller, he liked to entertain, while in private his lifestyle was frugal, a herring being usually the daintiest item on his lunch menu. He was fond of saying things that shocked people, a habit that could lead him to make such fatuous statements as: “Never fall out with the extreme men. They are extreme because they are extremely right!” Once, at a meeting of the Hierarchy, he denounced the danger to the faith of Ireland caused by the growing contributions of the great grazing interests to the ranks of the priesthood in the west: “St. Bernard once observed that when the chalices were of wood, the priests were of gold. Now that our chalices are of gold, God forbid our priests should be of wood.” “But, my dear lord,” remarked one of his colleagues, “what would you do?” “I would put the priests – and perhaps ourselves – for twelve months on a diet of Indian meal stirabout!” Invited by Michael Cusack and others to become patron of the planned Gaelic Athletic Association in 1884, Duggan declined due to illness, and suggested Thomas Croke, Archbishop of Cashel and Emily, in his place. The same year he requested the appointment of a coadjutor. Dr. John Healy, a Maynooth professor, was not his candidate of choice, and indeed was his polar opposite both in politics and in temperament. As a result, relations between the two ecclesiastics soon became strained. In later life Duggan presented a rather dishevelled appearance with his straggling white hair and a cassock bedaubed with snuff. He lived in primitive if not squalid conditions attended by a bare-foot servant girl. Bishop Duggan suffered a stroke while visiting a solicitor’s office in Dublin on 13th August 1896, and died two days later at Jervis Street Hospital. In deference to his wishes, he was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery beside his lifelong friend Cardinal Edward McCabe.

3 Comments

Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Jun/Jul 2017 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)Availing themselves of the opportunity presented by the state of anarchy prevailing in Ballinasloe in the months preceding the outbreak of civil war in 1922, on a night in May, some local members of the anti-Treaty I.R.A. mutilated and decapitated the bronze statue of the Third Earl of Clancarty that had stood on its plinth within a railed enclosure on Station Road since 1874. After sectarian slogans had been daubed on neighbouring walls, the severed head was carried into town and thrown through the plate-glass window of Rothwell’s shop on Dunlo Street.

Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Apr/May 2017 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)What picture is conjured up in our minds when we come across the word “manor”? A stately home deep in the heart of the English countryside? Perhaps the setting of a novel by Evelyn Waugh?

Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Oct/Nov 2016 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)Karen Hurley - Stage Crew Touching up the old Town Hall As a youngster back in the ‘50s I recall seeing a poster in a shop window announcing the imminent arrival at the Town Hall of Anew McMaster’s celebrated troupe of players to present a week-long feast of theatrical delights for the delectation of the good citizens of Ballinasloe. McMaster’s odd-sounding first name left me puzzled. Was he a newer version of an older McMaster? I wondered. It was only many years later I learned that Anew was a childish mispronunciation of Andrew that the great man had kept as his stage name. Born in Birkenhead in 1891, he ran away from home as a teenager, eventually making a career for himself in the London theatrical world. To avoid conscription, in 1915 he joined a touring company in Ireland, returning after the war to the London stage where he went on to win critical and popular acclaim for his interpretations of the major Shakespearean roles. In 1925 he formed his own company, touring Ireland almost annually for the rest of his life. Familiarly known as Mac, his company was regarded as the aristocracy of the fit-ups, small-scale enterprises whose performance patch was the villages and country towns. The fare Mac provided was predominantly Shakespearean, with a few thrillers thrown in as potboilers. Constraints of a tight budget meant that settings were minimalist, though the company was noted for their authentic costumes. A larger-than-life character, Mac was an actor-manager of the old school who played the lead part in virtually all his own productions. He was tall (six foot three), strikingly handsome, and had a superb voice with a remarkable vocal range. It was said that on one occasion he had silenced a drunken, disruptive audience by the sheer power and magnetism he exuded in the role of Othello. Nonetheless, in the judgement of contemporaries, he was an uneven actor, not above turning in a sub-standard performance at times. Never a great director, he was notorious for hiring cast members more on the basis of their willingness to work for less than the going rate than for their acting ability. Moreover, with advancing years his memory for lines began to fade, a difficulty he tried to overcome by having pages of the script unobtrusively attached to drapes and pieces of scenery. Drama wasn’t always confined to the stage of the Town Hall. In 1926 a fire at a makeshift cinema in Drumcollogher, Co. Limerick, resulted in 46 fatalities. Shortly afterwards, during one of McMaster’s presentations of “Macbeth” in Ballinasloe, as “the three weird sisters” cavorted round their bubbling cauldron, an electrical fault created an alarming visual effect. Whereupon a prankster in the auditorium shouted: “Drumcollogher!” A panic-stricken rush for the exits ensued. Fortunately, nobody was seriously hurt, although some ladies were reported to have lost their shoes in the stampede.

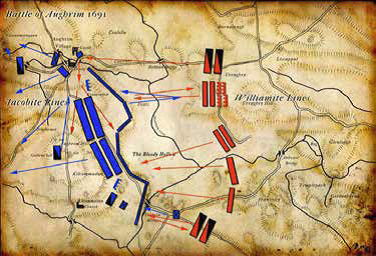

An Englishman successfully masquerading as a Monaghan-born Irishman, McMaster was married to Marjorie Willmore, a sister of Micheál Mac Liammóir, co-founder of Dublin’s Gate Theatre. When in Ballinasloe the couple always stayed at Hayden’s Hotel, while their two children, Christopher and Mary Rose, as well as the rest of the company, had to make do with pretty basic digs elsewhere in town. Mac disbanded his company in 1959, but continued acting up to his death three years later. The other fit-ups catered for less sophisticated tastes. Performances were generally in a tent on the Fair Green, sometimes in the Parochial Hall on Dunlo Hill, rarely in the Town Hall. A typical evening’s entertainment would consist of a melodrama featuring stock characters, some stand-up comedy, a few sketches replete with broad humour and local references, and a couple of songs. No “roadies” or stage hands were employed, so that the actors were required to do everything from publicising the show to erecting the performance tent. Versatility was evidently the name of the game, and the villain in the melodrama might appear later in the programme with a change of costume to give a rousing rendition of “A Nation Once Again”. If they found themselves in a place without a cinema, it would not be unusual for members of the company to visit a nearly town to view a popular film and return to present an improvised stage adaptation for the locals. Unable to compete with the novelty of television, the fit-ups went out of business over 50 years ago. In their day they performed a useful function in introducing and accustoming people to live theatre. It has been remarked that the absence of touring companies in recent decades has decimated the rural playgoers, with the result that anybody now setting out on tour would find it more difficult to attract an audience. The fit-ups had inherited the mantle of the strolling players of old, but left no successors. Provincial Ireland was the poorer for their passing Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Aug/Sept 2016 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)“Sign oh they died their lands to save At Aughrim’s slopes and Shannon’s wave.” Entrusted with the supreme command of the Jacobite armz in Ireland General Charles Chalmont arrived in Limerick from France on 9th May 1691 accompanied by 51 vessesls loaded with arms, ammunition, uniforms and provisions. At this stage in the War of the Two Kings the Irish suppoerters of King James had retreated to west of the Shannon, and were determined to hold the line of the river against an expected Willimite advance. Chalmont, officially known as the Marquis de Saint Ruhe (commonly though incorrectly rendered as Saint Ruth), was tall, well-built, and very ugly. In contrast to his title, his character seems to have been anything but saintly; contemporaries describe him as vain, strutting and insufferable rude. According to one source, he behaved so brutally towards his wife that she was obliged to appeal to King Louis XIV, who dispatched Chalmont to Ireland so that the poor woman might enjoy a respite from his reprehensible conduct. Relations between himself and Richard Talbot, James’s Lord Deputy, were said to be toxic. In the conflict between the Catholic King James II and his Protestand son-in-law William of Orange, the Gaelic Irish aristocracy and their follower had allied themselves with James in the hope that the effects of the Cromwellian cofiscations would be reversed and that they would be protected agains religious persecution. Ironically, the Pope was backing William and had advanced him a considerable sum of money as a war loan. Notwithstanding the support of France, the army of King James had suffered serious reverses in Ireland, particularly at the Battle of the Boyne the previous year. The Jacobites, however, did not regard their cause as beyond redemption, and they still looked forward to seeing the fortunes of war turn in their favour. It was in this mood that Chalmont set out for Athlone, where it was anticipated that the Williamites would attempt to effect a crossing of the Shannon. After the town had been pulverised by an intense and prolonged bombardment by Williamite artillery, the Jacobites concentrated their defensive positions on the west bank of the river. Seiying the opportunity presented by the low lever of the Shannon following a lengthy dry spell, on 30th June the Williamites launched a surprise attack by fording the river under cover of darkness. In the absence of Chalmont, who allegedly had taken time off to go hunting, the attackers under the Dutch General Godaard van Reede (later known as Count van Ginkel) quickly overran their opponents’ defences. Having suffered a humiliating defeat, a demoralised Jacobite army was forced to withdraw to Ballinasloe, losing nearly half its infantry to desertions on the way. Chalmont was blamed for the loss of Athlone and he knew it. Desperate to salvage his reputation, he disregarded the Lord Deputy’s oders to retreat to Limerick to await reinforcements from France, and decided to offer battle to the advancing Williamites at Aughrim. He may have been influenced in his choice of ground by hearing that O’Sullivan Beare had defeated a numerically superior English force at the site in 1602.

Sunday 12th July had begun with fog which had dispersed by midday as the armies stood facing each other on the opposite slopes of Kilcommedan and Urrachree, about three and a half miles sout-west of Ballinasloe. Ginkel commanded a mixed force of Englsih, Irish Portestand, Dutch, Danish and French Juguenot soldiers, approximately 20,000 strong, roughly the same in number as the army of his adversary, though the Williamites had the edge in artillery. The Jacobite position was a good defensive one since a bog separated them from their opponents, but could prove difficult in the event of their attempting a counterattack. The conflict raged from noon to sunset, during which time the Williamite assaults had been successfully repulsed until the tide of battle unexpectedly turned against the Jacobites. As he was about to lead a charge he hoped would clinch his victory, Chalmont was decapitated by a conon ball. Confusion ensured in the Jacobite ranks, for he had failed to communicate his battle plan to his subordinates. In another part of the field an equally disastrous event occurred. A narrow causeway led across the bog – approximating to the present-day Aughrim-Ballinasloe road – from the Williamite right to the Jacobite left flank. The Williamite General Mackay perceived this as a vulnerable point in his opponents’ defences, and resolved to lead a cavalry charge along the route. It used to be thought that a detachment of cavalry detailed to defend the causeway was treacherously withdrawn by their commander, Henry Luttrell, without engaging the enemy. Recent research suggests that this was not so, and that, on the contrary, a vigorous defence had been conducted until an order to retreat had come from further up the chain of command. Eventually the Williamites broke through, taking the main body of the Jacobites completely by surprise. Finding the enemy suddenly in their midst, they proved easy meat for their opponents. The result was a crushing defeat for the Jacobite cause on a field strewn with an estimated 4,000 corpses. Amongst the consequences of the battle were the Jacobite surrender on 28th August, the Flight of the Wild Geese, the expropiation of the landed property of those on the losing side, and the enactment of the Penal Laws. More than a century would pass before Ireland would again rise in arms. Aughrim is now no more, St. Ruth is dead, And all his guards are from the battle fled; As he rode down the hill he took a fall, And died the victim of a cannon ball” Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Apr/May 2016 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)It was a Tuesday evening, 14th July 1936. A motorist approaching the village of Aughrim sustained serious head injuries when the car he was driving collided with the parapet of a bridge. One of the first at the scene of the accident, Ballinasloe-based Dr. Gerry Coyne used his own car to convey the crash victim to Galway Central Hospital where he was pronounced dead on arrival. The deceased was identified as 45-year-old Patrick Hogan, a T.D. for the Galway constituency and a former Minister for Agriculture.

Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Dec '15 - Jan '16 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)In the years preceding the Second World War the Irish Folklore Commission launched a project whereby pupils in the country’s primary schools were asked to record items of folklore gathered from older members of their communities. Known as the Schools Collection, it reflected the sectarian and rural bias of its time in as much as only Catholic-run schools were invited to participate, hile Dublin City schools were also excluded. Material was grouped under 55 headings, with each school at liberty to choose as many or as few topics as it wished. The initiative was not, however, unanimously welcomed by our literary elite. For instance, the poet Patrick Kavanagh facetiously suggested that the money might be better spent supplying the bards of Ireland with free cigarettes!

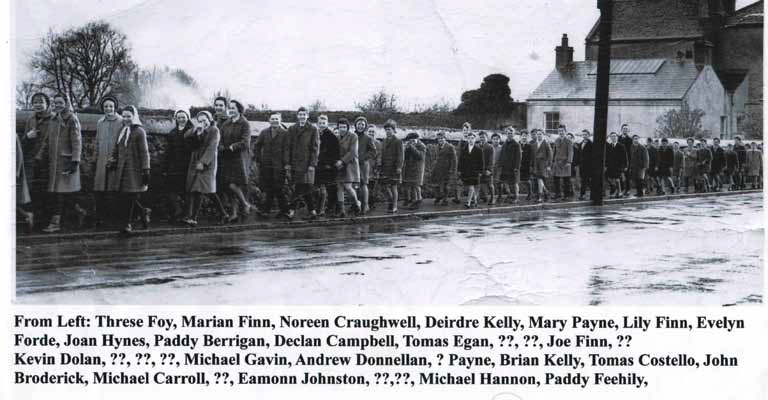

It is now possible by going online to peruse the local results of the scheme at dúchas.ie/en. Here it becomes apparent that of the two Ballinasloe schools involved, the Boys’ National and the Convent of Mercy, what the latter produced was by far the more interesting and detailed with 15 topics covered. Curiously, while all the sources are meticulously recorded, not one of the contributing pupils is mentioned. The Boys’ School chose 11 headings with 36 pupils named as contributors, of whom Joe Higgins of St. Joseph’s Place is believed to be the sole survivor. Willie Ward, the headmaster, wrote a perceptive introduction tracing the beginnings of national schooling in Ballinasloe to a location at the junction of Bridge Street and Main Street on a site at present occupied by the Oat Gallery apartment building. Later the school moved to what is now Jubilee Street before once more re-locating in 1910 to rooms at the back of the Town Hall. Ward believed that the dearth of local knowledge evident in his pupils’ submissions was probably due to the fact that the movement of population in towns was much more frequent than in rural areas. “In the surrounding countryside,” he wrote, “there are farms which have been in possession of the ancestors of the present owners for many generations, while in business premises in the town very few second generation owners exist. This accounts to a large extent for the fact that tradition is barren as far as Ballinasloe town is concerned.” In support of his argument he furnished a comprehensive list of 130 local businesses, only 17 of which were operated by a second generation. A reading of some of the pupils’ contributions prompts us to question the relationship between folklore and history. To take two examples, one boy writes that a Fr. Burke on a sick call on Christmas Eve in 1864 was drowned in the canal, while another relates that a priest drowned in the canal in the 1890s collecting for charity on a Thursday night. Fatal accidents at the Canal Basin were not uncommon, but there seems to be no evidence that a clergyman named Burke ever drowned there. Both pieces very likely had their origin in the following account based on a newspaper item dating from 1888: A watchman at Ballinasloe Gasworks reported hearing screams coming from the general direction of the adjoining Canal Basin sometime between 11.00p.m. and midnight on a date in January. The following morning a body was recovered from the water and taken to the Workhouse on Station Road where an inquest was later told that the deceased had been identified as Thomas Ryan, a 68-year-old former Catholic priest, a native of Loughrea, though not a member of the Clonfert diocesan clergy. He had done a stint on the American Mission, and on his return to Ireland had been silenced some nine years before his tragic demise because of chronic drunkenness. Ryan had recently arrived in Ballinasloe, taking lodgings in the Market Square, and had spent the day prior to his death cadging drink in local public houses. The comparison here between folklore and fact serves to remind us that the former is not history. What history involves is the reconstruction and interpretation of the past from its documentary remains, whereas folklore is concerned with communal memory, and memory, as we know, tends to blur and distort past events and to view them through the prism of present-day preoccupations and cultural values. Eighty years ago a story involving discreditable conduct by a cleric would not have been entertained. Should we then be surprised that the sad and sordid fate of a silenced priest had undergone a process of sanitization and transmutation by the time the event was recorded by schoolboys in the 1930s? Written by Brian Ciepieriski (Originally Published in Apr/May 2016 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)Even though Dr. Ada English was a member of Cumman na mBan and there was a strong Conradh Organisation in the town through the staff of St. Bridgids the towns peoples involvement in the turbulent events of 100 Easters ago appears somewhat muted. The East Galway Democrat of May 6th 1916 reported that all the local motorcars were commandeered ‘for the conveyance of the police to the Moyode farm (Athenry). It was feared that there might be a famine in bread but three local bakers motored to Mullingar on yesterday (Sunday) and secured yeast there which relieved the situation ‘as there is an abundance of flour in the town ‘. On account of the dislocation of traffic - eggs were sold on Saturday at 10s per score’ The paper mentions: ‘It was reported in Castlerea on Friday that Ballinasloe was in the hands of the Sinn Feiners and that the streets were wrecked and many people killed. Anxious mothers there sent motor cars for their daughters who were attending the Junior Mistresses Examination, to convey them home”. A bridal couple on their way to Dublin to spend their honeymoon there could only travel as far as Ballinasloe where they were ‘held up’ since Tuesday but they ‘left the town by car today for Athlone”. On May 13th the paper reported the arrest of Mr. J. O’Reilly, Manual Instructor in the Ballinasloe Technical School and Mr. Gaffney, Professor in St. Joseph’s College. Both men were handcuffed and handed over to the military authorities in Athenry as ‘suspected Sinn Feiners’. Taken in 1966, Creagh NS children walking to Mass in St Michael’s for the 50th Anniversary celebration of 1916. The photo was taken by the late PJ McGuane. 100 years on Ireland marks the centenary of the infamous Rising which occurred April 23rd 1916. St Brigid’s Hospital Heritage Group is spearheading a community based commemoration of this historic event alongside multiple groups and societies from the area.

Taking place on the afternoon of the 23rd of April, there will be several fun and educational activities happening. There will be a parade, a concert and a wreath laying ceremony! Also it is anticipated that camogie matches will be played in honour of Ada English Cumann. The library will host many interesting activities as well! There will be literature, pictures from the period, stories about the Rising, speakers and more. Jon Johnston from the group has stated ‘’we want this to be an inclusive that commemorates the events of 100 years ago in our area and the country, which helped shape where we are today’’. Written by Barry Lally (Originally Published in Feb/March 2016 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)The idea of linking Dublin to the River Shannon by means of a waterway had been first mooted as far back as the early 1700’s. It was not, however, until 1804 that the proposal came to fruition with the completion of the Grand Canal. An extension of the navigation to Ballinasloe had been proposed even before the main line had reached the Shannon. In 1807 the canal company decided to apply for a loan to construct a canal to Ballinasloe, which would be a continuation of the existing Grand Canal from Shannon Harbour.

Work began in 1824 with up to 1,000 men employed under the supervision of architect John A. Killaly. The canal was fourteen and a half miles long, twelve of which were through bogland, and had two locks, one at the junction with the Shannon and one at Kylemore. Because of the difficulties presented by the nature of the terrain, the project excited widespread interest internationally in engineering circles and attracted numerous visitors from abroad. Completed at a cost of £43,485, it opened to traffic on 29th September 1828. Initially, and for many decades thereafter, the barges were drawn by horses following a tow-path parallel to the waterway. (Grooves worn by the tow-ropes in the stonework are still visible beneath the arch of Poolboy Bridge.) By the 1840’s over 14,000 tons of goods were being carried annually and passenger boats were catering for a large number of travellers. In 1834, fly-boats had been introduced, which were less cumbersome than their predecessors. A boat travelled daily to and from Dublin, with extra services laid on during the October Fair Week. One of these boats could carry up to 80 passengers, with accommodation divided between a first-class and a second-class cabin. Passengers sat facing one another on upholstered benches attached to the walls. A long, narrow table occupied the centre of each cabin. Second-class passengers could buy stout and cider, but not wine or spirits, which were reserved for their fellow-travellers in first-class. Smoking was prohibited in every part of the vessel. Meals served on board were substantial, though scarcely calculated to appeal to fastidious palates. In 1843, a traveller on the Ballinasloe boat reported: “The dinner was a solid meal. It consisted of bacon, legs of mutton, beef, potatoes and beer, and was disposed of in such a manner as to show that those who partook of it must have right good stomachs. After dinner, whiskey punch supplied the place of coffee.” A trip from Dublin to Ballinasloe could be something of an endurance test to judge by the following account in an 1848 novel by Anthony Trollope: “I will not attempt to describe the tedium of that horrid voyage, nor will I attempt to put on record the miserable resources of those, who, doomed to a twenty-hour sojourn in one of these floating prisons, vainly endeavour to occupy or amuse their minds, but I will advise any, who, from ill-contrived arrangements, or unforeseen misfortune, may find themselves aboard the Ballinasloe canal-boat, to entertain no such vain dreams. Reading is out of the question. I have tried it myself, and seen others try it, but in vain. The sense of the motion, almost imperceptible but still perceptible; the noises about you; the smells around you; the diversified crowd, of which you are a part; at one moment the heat this crowd creates; at the next the draft which a window just opened behind your ears lets in to you; the fumes of punch, and the snores of the man under the table - these things alike prevent one from reading, sleeping or thinking.” Passenger services on the canal were withdrawn in 1852, a year after the opening of Ballinasloe railway station. The boggy nature of the canal banks meant that they were very vulnerable to malicious attacks, and numerous breaches were made in the 1830’s, usually by people living in the area who hoped to be employed in the repair work. The response of the authorities was to arrange for around-the-clock police patrols to discourage acts of sabotage. Three barracks to house the constables were erected at intervals along the route of the waterway. These continued to be manned up the 1860’s. Traffic in general merchandise on the canal ended in 1956. The Guinness barges, however, could still be seen chugging along the waterway up to a year before its closure in 1961. Rumour had it that the thirsty boatmen enjoyed an unofficial perk whereby they levied a toll of a few pints of porter on every cask of Guinness, which in those days was transported in wooden barrels. A gimlet was used to bore a hole, and a measure of beer was extracted, after which the keg was bunged with a sliver of timber hammered home with a mallet. Today parts of the canal have disappeared in bog workings, the section through Kylemore has been used to lay a light railway, and the Ballinasloe end has been filled in. The shell of the Guinness store, a mooring-ring in a wall, and the ruins of the harbourmaster’s house opposite the Shearwater Hotel are all that is left to remind us of what was once a busy traffic terminal and the westernmost limit of the Grand Canal. Written by Declan Kelly (Originally Published in Dec '15 - Jan '16 issue of Ballinasloe Life Magazine)William Frederick le Poer Trench, future fifth Earl of Clancarty, was barely 21 years old when he married Belle Bilton, a music hall dancer, in 1889. The marriage caused a sensation at the time and is worth recalling both as an example of true love and as a reminder of a remarkable lady. The fourth Earl was incandescent with rage and as the law of entail forbade him from disinheriting his son completely, he is said to have begun to have the timber on his estates felled in order to make them as worthless as possible. William Frederick le Poer Trench was forced to live off his wife`s music hall earnings with one newspaper noting that he was “no more capable of earning his living for himself than a cow is capable of composing a comic opera”. This process was halted when the illtempered fourth earl, collapsed and died in his library in London in May 1891.

The story handed down by all generations of townspeople tells how the new Earl and Countess arrived at Garbally and finding the gates locked against them, were obliged to scale the walls. It may seem unlikely, yet Belle Bilton was a remarkable lady who later reportedly performed a dance for the gentry of Connaught at Garbally House where she raised her right leg to the point where the big toe almost touched the lowermost light of a chandelier. They were scandalised and she was delighted. Being light on her feet and a stage acrobat of sorts, she would hardly have found the scaling of a wall too troublesome. Matters did not end there and the keys of Garbally were only handed over after the fifth earl was driven to Coorheen House in Loughrea to remonstrate with his stubborn mother. The new couple were held in disdain by Galway society to the point that at a hunt ball in 1893, most ladies left the floor when Frederick and his Countess began to dance. Despite this, Belle quickly became a firm favourite with the people of Ballinasloe and stories of her kindness to local people who were ill and her charity to the less well-off were in circulation until recent years. She even had her effigy cast by the wax museum in Dublin and won over the respect and affection of Queen Alexandra, the wife of King Edward VII. Belle was not long for this world, however, and after suffering from cancer for some years, died aged 39 on the last day of December 1906 at Garbally House, some 104 years ago! As her funeral slowly made its way from Garbally to the place of interment in the precincts of St John`s Church on Knockadoon, the hearse was filled to capacity with floral tributes and the tenantry of the demesne bore the coffin the entire journey. Every business was shuttered and virtually every man, woman and child in the district lined the streets to bow, curtsey, sob or throw flowers as the coffin passed. The outpouring of grief was both genuine and extraordinary and despite Belle`s humble origins, those who followed the coffin included Lord Ashtown, Lord Clonbrock, the local magistracy and every merchant of note. When the Gaelic League came to rename Victoria Street in 1946, they opted for `Duggan Avenue` in honour of the revered Bishop of Clonfert Dr Patrick Duggan. Had they chosen to rename it in honour of Belle Bilton, who lies within Knockadoon`s apex, there would surely have been few objections to honouring the memory of the simple but abundantly generous showgirl who danced her way into local hearts. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

The Town Team was set up by BACD Ltd. to revive the fortunes of Ballinasloe and its hinterland. With the main focus to build on the town’s many strengths, change existing negative perceptions and bring about measurable improvements in the town centre economy and its wider social value.

|

Ballinasloe Area Community Development Ltd.

Ballinasloe Enterprise Centre Creagh Ballinasloe Co. Galway |

All generic photos and images have been sourced and are free of copyright or are clip art images free of copyright. Photos of Ballinasloe have been donated by BEC. If you have any photos that you would like included on the website please email us

Copyright © All rights reserved, 2024 BACD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed